Slide Title

Write your caption here

Button

Slide Title

Write your caption here

Button

Slide Title

Write your caption here

Button

Slide Title

Write your caption here

Button

בס"ד

כ"ג בשבט, תשפ"ג

14 בפברואר, 2023

פרופסור מגנוס מרסדן

Professor Magnus Marsden

לפני כשלוש שנים יצר פרופ' מגנוס מרסדן קשר עם מערכת האתר "יהודי אפגניסטן בארץ ובתפוצות".

פרופ' מרסדן הנו פרופסור לאנתרופולוגיה חברתית ומנהל מרכז אסיה באוניברסיטת סאסקס באנגליה.

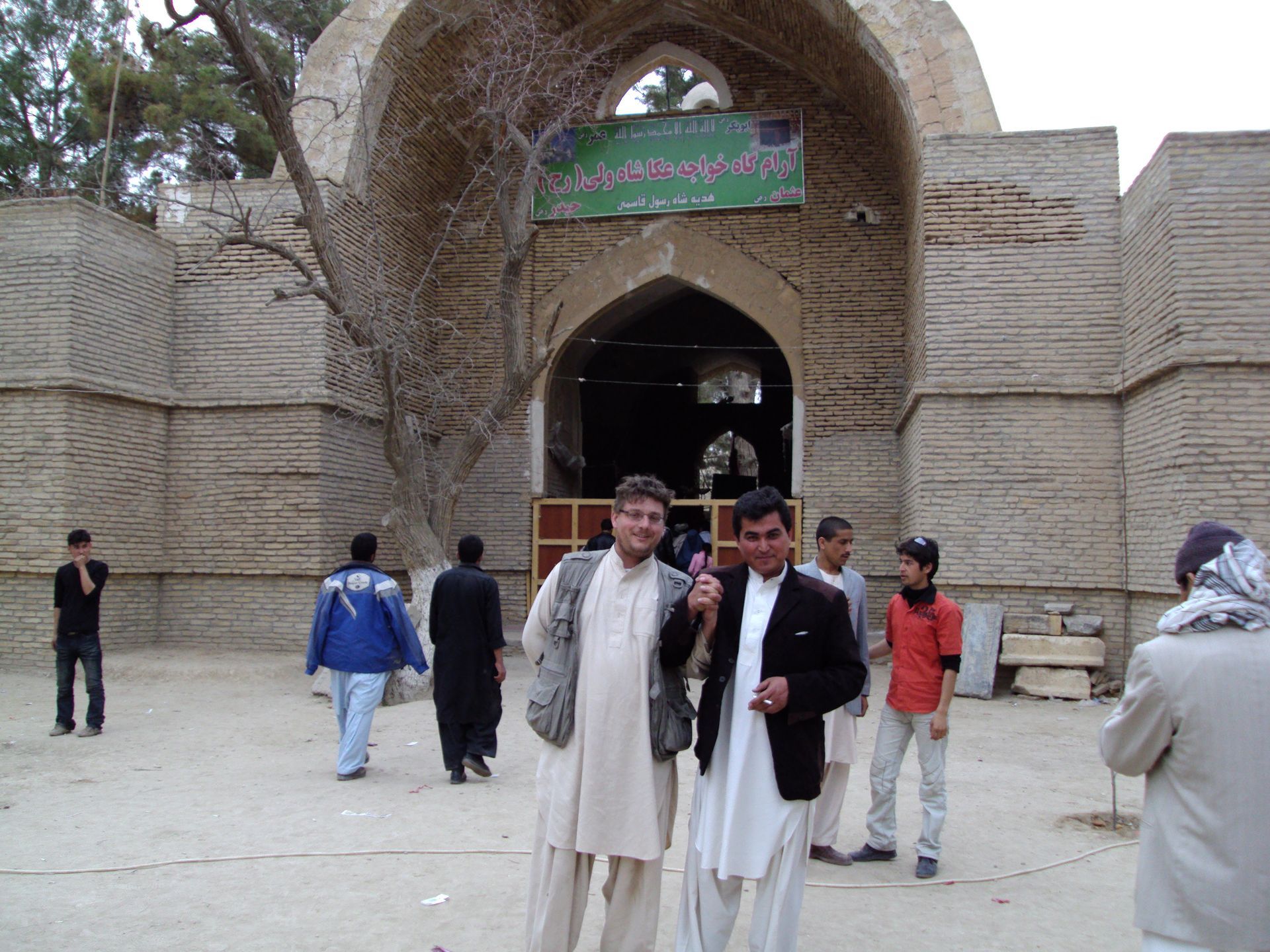

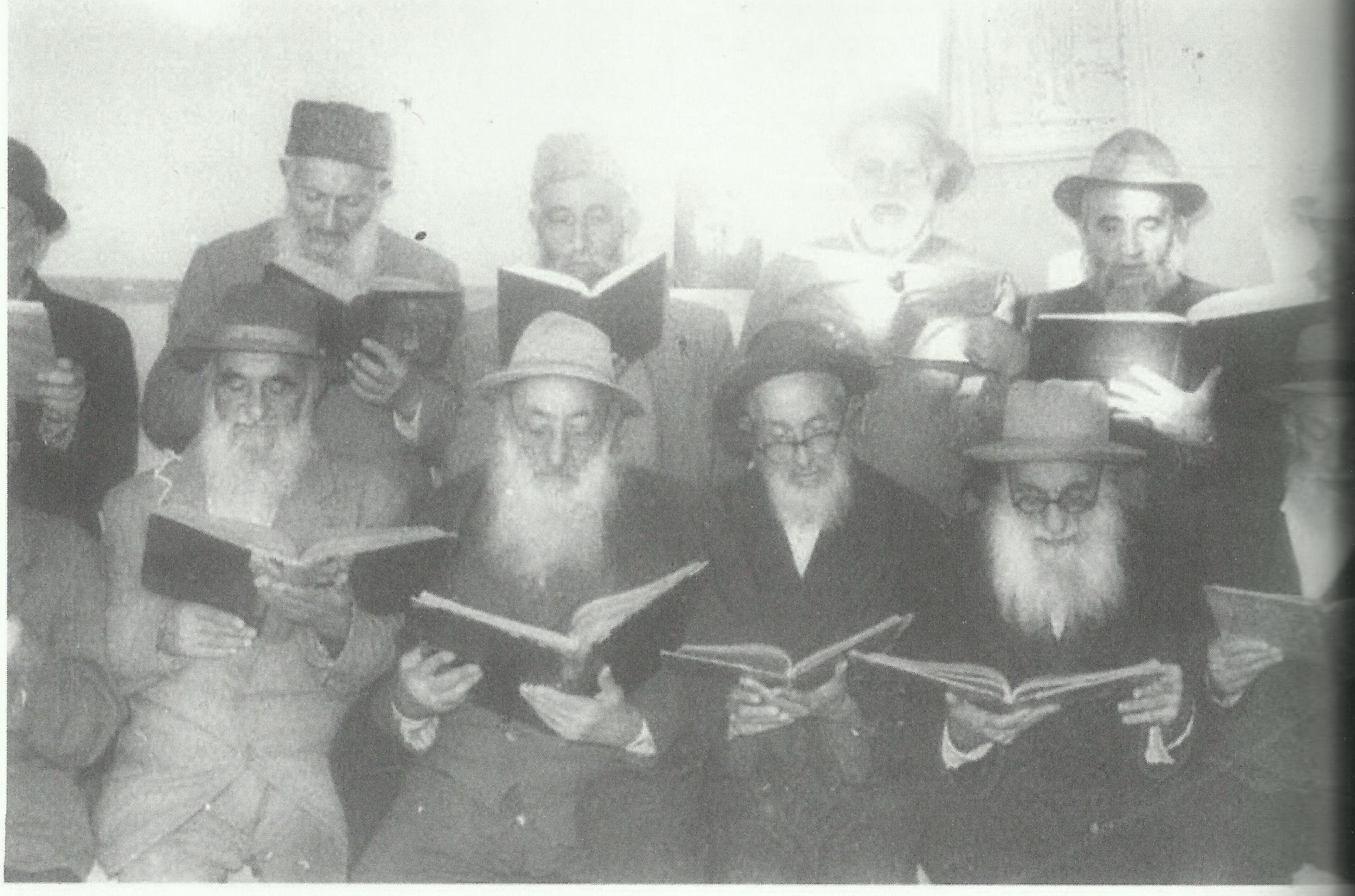

הוא דובר דארי, פושטו, בוכרית, טג'יקית ושפות נוספות המדוברות במרכז אסיה. במכתבו אלינו הביע פרופ' מרסדן את התפעלותו מהאתר שלנו ואף הביע את רצונו לבקר בישראל כדי לראות את הסביבה התרבותית בה נקלטו העולים מאפגניסטן ובוכרה, את השכונות בהן גרו, את בתי הכנסת, ואף לפגוש את האנשים, ככל שניתן. בראשית פברואר 2023 הוא הגיע לישראל וכמה מבני הקהילה נרתמו למשימת האירוח שלו: הרב רפאל בצלאל, ההיסטוריון בן-ציון יהושע רז, הגבאי ר' רפאל בקשי, זיוה קורט, מירי קורט, מרים וידל, זאב יקותיאל, אביגדור גרג'י, פנינה לואיס ואתי עמית. זיוה קורט ליוותה אותו לגלריית טובה אוסמן האפגנית בתל אביב. זאב יקותיאל ואתי עמית טיילו עמו בשכונת הבוכרים, הרב רפאל בצלאל ור' רפאל בקשי פגשוהו בבית הכנסת "ישועה ורחמים", ואביגדור גרג'י טייל עמו בשכונת שפירא ובבתי הכנסת שם, עם דגש על בית הכנסת "ישועת ישראל". לבקשתו גם הפגשנו בינו לבין בני הקהילה הבוכרית.

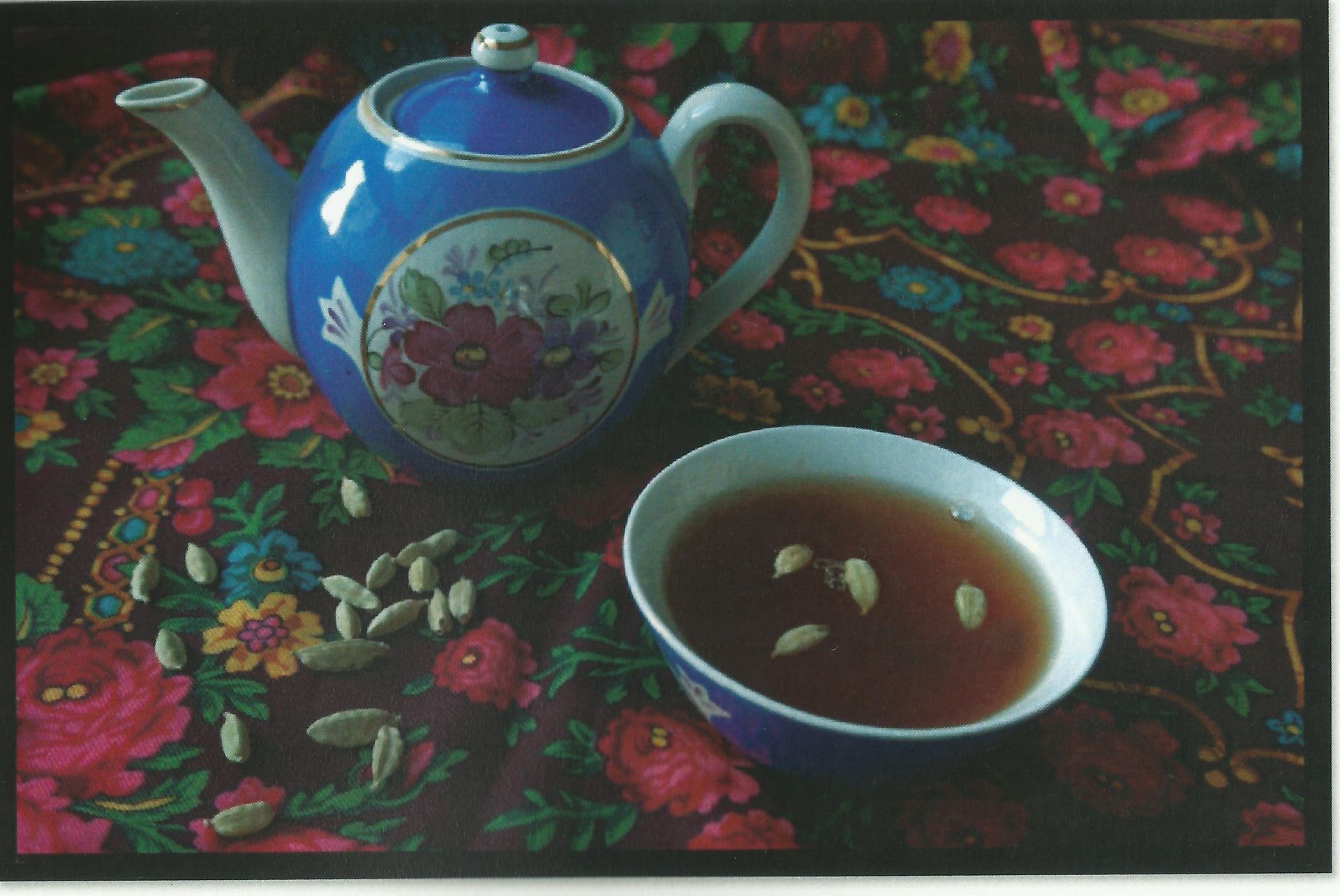

החלטנו לערוך לכבודו סעודה אפגנית, ולשם כך הזמנו את השפית הדגולה מירי קורט. מירי הפליאה ביכולותיה. את הסעודה הנהדרת שהכינה פתחנו בברכות לאורח בשפת הדארי, ואח"כ נהנינו מפלוב ק'בולי נהדר, מבחש בוכרי ומטעמים כמו סיר באדם ג'אן, נאן באזארי שהכין זאב יקותיאל, אש-תנור שהביאה מרים וידל ועוד ועוד. קינחנו בצ'אי אדמדם ובקלאווה. לסיום הענקנו לאורח את חוברת "בואי כלה" שהפיק מוזיאון ישראל בעקבות התערוכה אותה אצרה נעם ברעם.

אנו מקווים שבאירוח פרופ' מרסדן בו פתחנו את לבבנו לאורח המכובד, כיבדנו את מסורת אבותינו במנהג הכנסת אורחים כמקובל עליהם. מי יתן והדבר יביא לקירוב לבבות.

להלן דבריה של מירי קורט לאחר אירוח פרופסור מרסדן:

ביום חורפי בהיר וקר לקחתי את האוטובוס מהתחנה המרכזית בראשון לציון לירושלים, ונסעתי לביתה של אתי עמית היקרה, שם אמורים היינו לפגוש פרופסור אנגלי, ראש החוג ללימודי אסיה באוניברסיטת סאסקס, מר מגנוס מרסדן. הדמיון אמר שנפגוש איש אנגלי צנום יבש וקר, המציאות היתה איש אנגלי, ביישן, צנוע וחביב למדי. תהיתי לעצמי איזה עניין מצא הפרופסור בעדה שלנו, במורשתה ובאנשיה, ומה משך אותו לבקר בכל שכונה וכל בית כנסת של בני העדה האפגאנית והבוכרית . אך הפרופסור הקשיב יותר ודיבר פחות, ורק מאוחר יותר מהדברים שכתב הסתבר שהמשיכה שלו למדינות האזור ההוא של העולם התחילה עוד כשהיה נער צעיר .

אני מחכה למפגש נוסף עם אכאיי פרופסור , בתקווה שבפעם הבאה אוכל לשאול אותו על הראט ועל האנשים שפגש שם

ולהלן דבריה של זיוה קורט:

לגלריה של טובה אוסמן, אחת הגלריסטיות הוותיקות והמצוינות הפועלות בסצנה המקומית (גלריה טובה אוסמן,

בן יהודה 100, תל אביב) הגענו ביום השני לשהותו של פרופ' מרסדן בארץ.

על טובה אוסמן המליצו ידידיו של פרופ' מרסדן בבריטניה.

במפגש בן מספר השעות, השיחה נסובה בעיקר על בני משפחתה של אוסמן ועל הקורות אותם באפגניסטן, העלייה ארצה, הקשרים הגניאלוגיים ועוד. היה מעניין!

*****

פברואר 2023

לאחר עזיבתו את הארץ, שלח אלינו פרופ' מרסדן מאמר המסביר כיצד התפתחו בו הסקרנות והעניין לגבי ארצות מרכז אסיה. להלן הכתבה בעברית, הכתבה המקורית באנגלית הנה בהמשך הכתבה.

מאת פרופסור מגנוס מרסדן

פרופסור לאנתרופולוגיה חברתית

מנהל מרכז אסיה

אוניברסיטת סאסקס, אנגליה

Magnus Marsden

Professor of Social Anthropology

Director of Sussex Asia Centre

Department of Anthropology

School of Global Studies

University of Sussex

ב- 5 בספטמבר, בהגיעי לגיל 18 התחלתי במסע אשר יעצב את מסלול חיי.

החלטתי לקחת " שנת גישור "בין בית הספר התיכון לאוניברסיטה ופניתי לארגון הנקרא "פרויקט אמון" השולח בוגרי תיכון ללמד אנגלית במשך שנה אחת בארצות ברחבי העולם.

מאז גיל 15 חלמתי לבקר בפקיסטן, במיוחד באזור הצפוני ההררי של מחוז צ'יטראל (Chitral). מה בדיוק עורר את סקרנותי לגבי פקיסטן לא ברור לי לגמרי. כנער מתבגר הייתי להוט אחרי משחק הקריקט, ובמיוחד מהופנט ע"י השחקנים המוכשרים מפקיסטן. כמו כן פיתחתי עניין במוזיקה הסופית הפקיסטנית המסורתית הנקראת קוואלי (Qawali) ובמיוחד בזו של המאסטרו נוסראת פטה עלי חאן (Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan).

בין ספטמבר 95 ל-96 לימדתי בבית ספר כפרי בהרי מחוז צ'יטראל בפקיסטן. בשנה זו למדתי את שפת ה"חוואר" (khowar) בה דיברו הכפריים. אזור צ'יטראל היה גם ביתם של אלפי פליטים מאפגניסטן וטאג'יקיסטן, וכך למדתי את השפות דארי וטאג'יקי.

כאשר לא לימדתי, ביליתי זמני בטיולים בין הכפרים היפים באזור, ובאירועים מוזיקליים שנערכו בגנים קרירים שצוננו ע"י מעיינות זורמים ובצילם של עצי תות, תפוח ומשמש שכמובן גם מפירותיהם נהניתי.

כשחזרתי לאנגליה התחלתי ללמוד אנתרופולוגיה וארכיאולוגיה בקולג' טריניטי, אוניברסיטת קיימברידג'. במשך 3 שנות לימודי ביליתי כל קיץ בצ'יטראל, מבקר את חברי, משפר את כישורי השפה שלי ומדריך עבודות מחקר במסלול בוגרים. החלטתי שהדרך הטובה ביותר להבין את המקום היא לעשות דוקטורט באנתרופולוגיה חברתית. ב - 1999 התחלתי ללמוד על הזהויות המוסלמיות של תושבי המקום, מה שהביא לכך שגרתי באזור צ'יטראל במשך 18 חודשים, בין אפריל 2000 לספטמבר 2001.

עזבתי את פקיסטן לכתוב את ממצאי השדה שלי ימים אחדים אחרי מתקפת הטרור של 11 בספטמבר על ארצות הברית. ב-2005 עבודת הדוקטורט שלי פורסמה בספר שיצא לאור ע"י אוניברסיטת קיימברידג' תחת הכותרת Living Islam: Muslim Religious Experience in Northern Pakistan

הספר מאתגר את הרעיון שצורות שונות של מוסלמיוּת-מושפעת-טליבן שליטות בחיי האזור, ומראה את הדרכים בהן הכפריים עמם חייתי העריכו תהליכי חשיבה ביקורתיים ויצירתיים. הספר תיעד את חיבתם של הכפריים לדיונים, שירה ומופעים מוזיקליים.

כאשר עבדתי על הדוקטורט והספר שלי, אפגנים וטג'יקים רבים שהכרתי בצ'יטרל חזרו למכורתם. תבוסת הטליבן בשנת 2001 והשיפור במצבם של הטג'יקים אחרי סיום מלחמת האזרחים ב1998, משמעותה הייתה שחזרה הביתה עבור פליטים הינה אפשרית. אני הייתי סקרן לדעת כיצד פליטים שהכרתי בפקיסטן מסתגלים לחיים בארצות מולדתם. כדי למצוא את התשובה, יצאתי בנובמבר 2005 למסע מדושנבה בטג'יקיסטן לפשאוואר בפקיסטן דרך צפון אפגניסטן וקבול. במסע במוניות שירות וטרמפים בין כפרים מרוחקים פגשתי אנשים רבים שהכרתי בפקיסטן בשנות ה-90. ראיתי כיצד רבים היו עתה מעורבים במסחר חוצה גבולות בין פקיסטן, אפגניסטן וטג'יקיסטן. באותה עת התקשורת נשלטה ע"י מראות של אסלאם קיצוני בייצוגן של אפגניסטן ומרכז אסיה. עם זאת האנשים שהכרתי היו מיומנים בחציית גבולות ובהסתגלות לחיים בארצות השונות בהן עברו במסעותיהם. במהלך העשורים הבאים ביליתי עם סוחרים באפגניסטן (במיוחד בקונדוז, מזר-א-שריף, קאבול והראט) ובמרכז אסיה (במיוחד בקוג'נד ודושנבה בטג'יקיסטן אך גם בבוכרה אוזבקיסטן) כמו גם באזורים בם נתבצע המסחר עצמו (מסין לרוסיה, אוקראינה ואף לונדון). יכולתם של הסוחרים לעבוד באזורים הפכפכים פוליטית והדרכים בהן בנו יחסי אמון שגישרו על פני אלפי קילומטרים הקסימה אותי. כתבתי שני ספרים אודות סוחרים אלה (Trading Worlds: Afghan Merchants across Modern Frontiers and Beyond the Silk Roads: Mobility, Commerce and Mobility across Eurasia)

(עולמות מסחר: סוחרים אפגנים מעבר לגבולות מודרניים ; מעבר לדרכי המשי: ניידות, מסחר, וניידות מעבר לאירואסיה). שני הספרים הדגישו את קשריה של אפגניסטן לעולם הרחב ואתגרו את אלה אשר תיארו אותה כאזור מרוחק ומפגר.

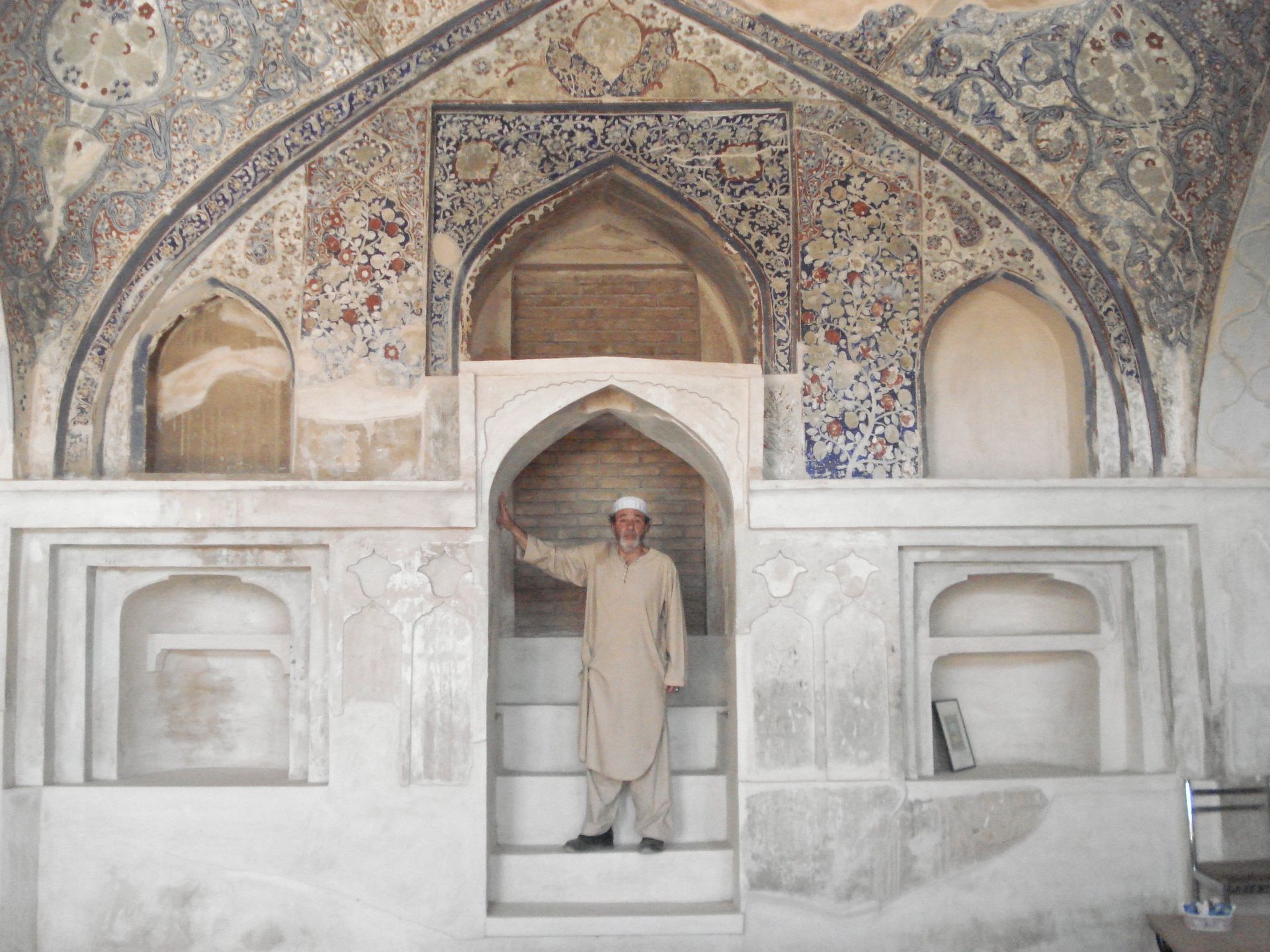

שהותי עם סוחרים וקריאה אודות ההיסטוריה של המסחר באזור הביאה לתשומת ליבי את התפקיד ההיסטורי שמילאו המיעוטים הדתיים באזור ובדינמיקה של המסחר בדרך המשי. ביקרתי במקדשים סיקים והודים בקאבול. ביקרתי בבית הכנסת המפורסם "מולא יואב" בהראט, וביליתי בשכונה היהודית בבוכרה. ידידיי מאפגניסטן סיפרו לי סיפורים כיצד כילדים הם קיבלו סוחרי שטיחים אפגנים בכפריהם בצפון אפגניסטן. פגשתי סוחרים סיקים מאפגניסטן סוחרים לצד אפגנים מוסלמים במוסקבה, אודסה וסין. הייתי להוט לדעת יותר אודות קורותיהם של הקהילות ששיחקו תפקיד כה מרכזי בהיסטוריה של האזור, בכלכלה ובתרבות שלו . כיצד שמרו על זהותם בארצותיהם החדשות ובערים אליהם עברו? האם שמרו על קשרים עם ערי המוצא שלהם באפגניסטן ובמרכז אסיה?

בשנה האחרונה ביקרתי בקהילות של סיקים והינדים מאפגניסטן בלונדון, של יהודים מאפגניסטן ומרכז אסיה בניו יורק, ולאחרונה בישראל. היה זה מאיר עיניים לראות את המאמצים שקהילות אלה השקיעו כדי לבנות מוסדות – החל מאתרי אינטרנט תרבותיים ושווקים עד בתי כנסת ומקדשים – שאפשרו להם לשמר את עברם המיוחד, להיטמע במקומותיהם החדשים, ולתחזק קשרים חברתיים אחד עם השני.

זהו , אם כן, הנו סיפור (מאד קצר) של מישהו שגדל בכפר בצפון אנגליה, חי בכפרים מרוחקים בפקיסטן, בילה בשווקים ההומים של אפגניסטן ומרכז אסיה, ופסע ברחובות ההיסטוריים של ירושלים, בוכרה והראט. חשוב מכל, הסיפור מגלה את הכוח המחבר של התרבות וההיסטוריה של אפגניסטן ומרכז אסיה ושל האנשים הנפלאים באזור זה.

***

On September 5th at the age of eighteen, I embarked on a journey that would shape the course of my life. Having decided to take a ‘gap year’ between school and university I applied to an organisation called ‘Project Trust’ that sends school leavers to teach English for a one year spell in countries across the world. Since the age of 15, I had dreamed of visiting Pakistan, especially the country’s northern and mountainous Chitral region. What exactly led to my curiosity in Pakistan is not entirely clear. As a teenager, I was a passionate follower of cricket and mesmerised by skilful players from Pakistan in particular. I also developed an interest in Pakistan’s tradition of Sufi devotional music, known as Qawali, especially in the form practiced by the maestro Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Between September 1995 and 1996, I taught English in a school in a village in the mountainous Chitral district of Pakistan. During the year, I learned the language Khowar that the villagers spoke. Chitral was also home to thousands of refugees from both Afghanistan and Tajikistan, so I also began to learn Dari and Tajiki. When not teaching, I spent my time walking between the region’s beautiful villages and attending musical events organised in gardens kept cool by fast flowing streams and the shade of mulberry, apple and apricot trees, the fruits of which I also enjoyed.

On my return to the UK, I studied Anthropology and Archaeology at Trinity College, the University of Cambridge. During the course of my three-year degree, I spent each summer in Chitral, visiting my friends, improving my language skills, and conducting research for undergraduate dissertations. I decided that the best way to understand the place would be to do a PhD in Social Anthropology. In 1999, I set out to study the Muslim identities of people living in the region; this involved me living in Chitral for 18 months between April 2000 and September 2001. I left Pakistan to write-up my fieldwork findings days after the September 11th terrorist attacks on the USA. In 2005, my PhD was published as a book by Cambridge University, entitled Living Islam: Muslim Religious Experience in Northern Pakistan. The book challenged the idea that Taliban-inspired forms of being Muslim dominated life in the region and showed the ways in which the villagers with whom I had lived valued creative and critical thought processes. The book documented the villagers’ love of debate, poetry, and musical performance.

As I was working on my PhD and book, many of the Afghans and Tajiks I had known in Chitral returned to their home countries. The defeat of the Taliban in 2001 and the improving situation of Tajikistan after the end of the civil war in 1998 meant return home was possible for refugees. I was interested to know how refugees I had known in Pakistan were adapting to life in their homelands. In order to find out, I set off in November 2005 on a road trip from Dushanbe in Tajikistan to Peshawar in Pakistan by way of northern Afghanistan and Kabul. Travelling in shared taxis and hitching lifts in remote villages, I met many men I had known in Pakistan in the 1990s. I saw how many were now engaged in cross-border trade between Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. Media representations of extremist Islam dominated the representation of Afghanistan and Central Asia at the time. Yet the people I knew were skilled in crossing borders and adapting to life in the very different countries across which they moved. Over the coming decades, I spent time with these traders in Afghanistan (especially in Kunduz, Mazar-e Sharif, Kabul and Herat) and Central Asia (mostly in Khujand and Dushanbe in Tajikistan but also in Bukhara, Uzbekistan) as well as the many settings in which they did business (from China to Russia, the Ukraine and even London). The ability of the traders to work in politically volatile settings and the ways in which they built relationships of trust that spanned thousands of miles fascinated me. I write two books about these traders (Trading Worlds: Afghan Merchants across Modern Frontiers and Beyond the Silk Roads: Mobility, Commerce and Mobility across Eurasia). Both books emphasised Afghanistan connections to the wider world and challenged those who depicted it as a remote and backward space.

Spending time with traders and reading about the history of trade in the region brought my attention to the historic role that religious minorities had played in the region and in the dynamics of Silk Road trade. I visited Sikh gurdwaras and Hindu temples in Kabul. I visited the famous Yu Aw synagogue in Herat. And I spent time in the Jewish mohalla of Bukhara. My friends from Afghanistan told me stories of how as children they had received Jewish carpet traders in their villagers in northern Afghanistan. I met Sikh traders from Afghanistan trading alongside Afghan Muslims in Moscow, Odessa and China. I was keen to know more about what had happened to communities that had played such a major role in the region’s history, economy and culture. How had they maintained their identities in the new countries and cities to which they had moved? Did they maintain links with their cities of origin in Afghanistan and Central Asia?

Over the past year, I have been visiting communities of Sikhs and Hindus from Afghanistan in London and Jews from Afghanistan and Central Asia in New York and most recently Israel. It has been truly eye opening to see the efforts that these communities have made to build institutions – from cultural websites and markets to synagogues, gurrdwaras and temples – that enable them to treasure their unique backgrounds, adapt to new settings, as well as maintain social relationships with one another.

This, then, is (a very brief) story of how someone brought up in a village in northern England has lived in remote villages in Pakistan, spent time in the bustling markets of Afghanistan and Central Asia, and walked along the historic streets of Jerusalem, Bukhara, and Herat. Most importantly, the story reveals the connective power of the culture and history of Afghanistan and Central Asia and of these region’s wonderful peoples.

***

הביקור בארץ

זיוה קורט ומגנוס מרסדן, טובה אוסמן ומגנוס מרסדן בגלריה של טובה אוסמן

****

ארוחה אפגנית

-

השקת לחיים

***

בבית הכנסת ישועה ורחמים בשכונת בית ישראל בירושלים

***

שכונת שפירא בתל אביב ובית הכנסת האפגני "ישועת ישראל"

המדריך אביגדור גרג'י

***

העיר הראט

הכתבה שלהלן מאת פרופ' מרסדן, מתארת את שעבר על אפגניסטן בשנים האחרונות עם חילופי המשטר שם.

ביקשנו ממנו שיכתוב עבורנו את הערכותיו ותובנותיו לגבי העתיד הצפוי למדינה.

הכתבה לפניכם:

אפגניסטן לאחר אוגוסט 2021

מאת פרופסור מגנוס מרסדן

פרופ' לאנתרופולוגיה חברתית אוניברסיטת סאסקס

תרגמו לעברית דוניה מאיר ומרים וידל

Afghanistan After August 2021

Magnus Marsden

Professor of Social Anthropology, University of Sussex

אפגניסטן לאחר אוגוסט 2021

לקראת מאי 2021 היה ברור לחלוטין שממשלת אפגניסטן והמדיניות שהיא מייצגת

לא יחזיקו מעמד ויקרסו תוך שנה. עד אז הסיכוי הטוב ביותר לממשלה היה שצבא

אפגניסטן יהיה חזק דיו לשלוט ברוב שלא לדבר על כל רחבי אפגניסטן. אולם עם הפסקת הסיוע

הטכני שהגישה ארה"ב לצבא, והנתונים המוגזמים על גודלו של צבא אפגניסטן, קטנו הסיכויים

שממשלתו של אשראף גאני תצליח לשלוט בריכוזי הערים, ובוודאי שלא על העורף הכפרי.

על רקע זה הטאליבן דהר בכל רחבי המדינה ביולי אוגוסט וכבש את קבול באוגוסט 2021.

חל שיפור ברמה הכללית של ביטחון באפגניסטן מאז העזיבה של הכוחות הבינלאומיים ושובם של הטליבן לשלטון בקבול. כעת אפשר לנסוע ביתר קלות לחלקי ארץ נוספים מאשר בשנות ההתקוממות של הטליבן נגד NATO וממשלות אשרף גאני וחמיד קרזאי. מצד שני, באותו הזמן הטליבן נהגו תמיד לרדוף באכזריות אחרי אויביהם. מאז נטילת השילטון על ידי הטליבן ב2021 , מפקדי צבא, אנשי ביטחון לשעבר ומתנגדים גלויים של משטרם כולל חברות ממשלה לשעבר ועיתונאים, עונו ונהרגו.

בתחום הכלכלה הטליבן הוריד את רמת השחיתות בגבולות אפגניסטן, דבר שהקל מאד

על המסחר בין אפגניסטן למדינות אסיה. יחד עם זאת סנקציות בינ"ל שהוטלו על הטליבן

גרמו להרס הכלכלה, הגבירו את האבטלה ודרדרו משפחות רבות לרמה חמורה של עוני.

הסנקציות בתחום ההומניטרי הובילו לירידה דרמטית בהגשת עזרה רפואית, ובבתי חולים

צוותים רבים עבדו ללא קבלת משכורת.

היו תקוות רבות שהטליבן ינהל כעת את המדינה והחברה בדרך שונה מזו של תקופת

כהונתם הראשונה [1996-2001]. גורמים בינ"ל תמכו בשיחות בתיווכו של הדיפלומט האמריקאי

זלמן חאליזאד ואולם תקוות אלה התנדפו במהרה. שוב הוכח שהתרבות האפגאנית [מה

שלא תהיה] היא שבטית ושמרנית ומסבירה את כישלונה של המעורבות המערבית

ב 20 השנים האחרונות.

כמו בשנות ה 90, נשות אפגניסטן היום סובלות מהמדיניות של הטליבן. מיד עם כיבוש אפגניסטן הטליבן אסרו כניסתן של נערות לבתי ספר תיכוניים. הם תרצו זאת במצב הבטחוני. מיד אחרי זה נאסר על נשים ללמוד באוניברסיטאות וגם נאסרה העסקתן במגוון עבודות. הוגבלה תנועתן של נשים במרחב הציבורי. ב 2021 נשים אפגניות עסקו במגוון רחב של עבודות, נהנו

מבילויים במסעדות, בבתי קפה ובפארקים. ב 2023 נשות אפגניסטן הורשו לצאת מבתיהן

רק בחברתו של קרוב משפחה ממין זכר. אפילו נאסר עליהן לבקר במרכזי בילוי שנועדו לנשים.

מידי פעם יש חילוקי דעות בהנהגת הטליבן, בעיקר בנושא של חינוך הנערות אך גוברת ידם של השמרנים בהנהגה.

האם יש אלטרנטיבה לטליבן?

רוב ההפגנות נגד הטליבן בתוך אפגניסטן אורגנו והובלו ע"י נשים. נשים אקטיביסטיות נעצרו

ונכלאו כאשר התעמתו עם ההגבלות של הטליבן על חינוך ותעסוקה לנשים.

בחדשים הראשונים של השתלטות הטליבן על אפגניסטן הייתה ציפייה שיהיו במדינה

הרבה תנועות של מרד בטליבן. אחמד מסעוד בנו של שר ההגנה האפגני, שהיה

אנטי טליבן מובהק, רצה לארגן את "חזית ההתנגדות הלאומית" [NRF] ולהגן על

עמק פאנג'שיר. מדינאים ואנשי צבא מהממשל הקודם הצטרפו אליו. אחרי כשלון המו"מ בין מסעוד והטליבן, כוחות הטליבן נכנסו לפאנג'שיר באוגוסט 2021. הם דיכאו באכזריות את האוכלוסייה המקומית ואילו אחמד מסעוד ותומכיו ברחו בהליקופטר לשכנה טג'יקיסטן. משם הם ממשיכים בהצהרות נגד הלגיטימיות של ממשל הטליבן וקוראים להקמת ממשלה מוסלמית מתונה שבה יובטחו זכויות הנשים.

ה NRF מעורב גם בפעולות גרילה בצפון המדינה. אבל הם לא הגיעו לשום הישג משמעותי, ומפקדי צבא חשובים שלהם נהרגו בחודשים האחרונים. מלבד ה NRF גם קבוצות אחרות נלחמו בטליבן בקנדהאר, קבול וערים נוספות. בהיעדר עזרה ותמיכה בינ"ל ובהעדר שליטה על טריטוריה באפגניסטן, הפגיעה שלהם באחיזה של הטליבן במדינה הינה מינימאלית.

בו בזמן שתנועות הטוענות להיות בעד דמוקרטיה וזכויות האדם היו במקרה הטוב הפרעה מועטה, ISIS – KHORASAN - דעא"ש חורסן יצאה בהתקפות קטלניות שהרגו ופצעו עשרות אזרחים אפגניים. הם שמו למטרה במיוחד מוסדות דת של המיעוטים הדתיים, התקפות נגד מתפללים שיעים ומתפללים משבט "הזרה" במסגדים בקבול, הראט וקנדהר, והרגו מספר סיקים והינדוים מהמעטים שנשארו בארץ. הידועה ביותר הייתה ההתקפה על גורדווארה של הסיקים ביוני 2022 . גורמים בינלאומיים נוטים לתמוך בדעא"ש חורסן (אם כי מרחוק) כאיום על ממשלת הטאליבן וכוחות הבטחון שלהם.

הקשיים בהם נתקלות תנועות ההתנגדות אינם מצטמצמים רק בקשיי לחימה. ההנהגה הקודמת של אפגניסטן מפוזרת בכל רחבי העולם, בתורכיה ובמדינות המערב. אפגנים רבים במדינה ומחוצה לה רואים בממשלה שהונהגה בידי אשרף גאני ממשלה מושחתת. תמונות של בתיהם המפוארים הופצו ברשתות החברתיות. לכן לא מפליא שרבים בתוך ומחוץ למדינה רואים את שורש הבעיה בהנהגה הקודמת של אפגניסטן אשר הביאה לחזרת הטליבן ונפילת הממשלה הקודמת. מנהיגיה הקודמים של אפגניסטן שנמלטו באוגוסט 2021 חיים ברווחה ובנוחיות באיסטנבול, אנקרה ודובאי ואילו תומכיהם נאלצים להסתגל לשלטון הטליבן או לחיי גלות. בתוצאה מכך מנהיגים פוליטיים של אפגניסטן המתנגדים לטליבן חסרים רמה כלשהיא של לגיטימיות לעומת היחס אליהם בתחילת שנות ה 2000.

יש קשרים רופפים מאד בין מתנגדי הטליבן בינם לבין עצמם, בין הארגונים ובין הבודדים.

הם נבדלים מהאספקט של אינטרסים כלכליים ופוליטיים, בשילוב עם הפיצול של הכיתות

הדתיות והאתניות. למשל ההבדל בין מנהיגים מייצגי הפשטונים לבין הטאג'יקים

הוא חד מאד. יש מנהיגים הטוענים שבעיות אפגניסטן נובעות משיטת השלטון הריכוזית. אחרים מאשימים מנהיגים אלה כתומכי בדלנות.

מנהיגי אופוזיציה בחו"ל מתווכחים על עתידה של אפגניסטן, שנאסר עליהם לבקר בה

ושיש להם השפעה מזערית על הנעשה בה. כתוצאה מכך גורמים בינ"ל שוללים כל אפשרות

שמנהיגים אלה יארגנו אי פעם אופוזיציה אפקטיבית מול הטליבן.לאור זה פרשנים מאפגניסטן וגורמים בינ"ל מקווים שיקום דור חדש של פוליטיקאים באפגניסטן שיוכלו להתמודד מול הטליבן בעתיד.

הנשים האפגניות משחקות תפקיד ראשי בהתארגנות פוליטית בחו"ל. אולם לסגירת

האוניברסיטאות ובתי הספר בפני הנשים תהיה השפעה רבה על הפרופיל המגדרי של

הדור הבא של מנהיגי אפגניסטן.

התחזית לשנים הבאות הינה עגומה. חוסר ההתעניינות בנעשה באפגניסטן בצל המלחמה באוקראינה, הדומיננטיות של הטליבן והשחיתות והפיצול של האופוזיציה חסרת הלגיטימיות בעיני האוכלוסייה, כל זה הופך את האפשרות לשינוי ממשל באפגניסטן לבלתי סביר.

כמו במקרים רבים בהיסטוריה של אפגניסטן, היעדר קשרים בינ"ל והעדר דינמיקה להשגת כח

ורווחה, פירושו שעתידה של המדינה נשען על היכולת של אוכלוסייתה ידועת הסבל

לשאת ולסבול את הנסיבות הקשות ולבנות גשר בין חלקיה.

Afghanistan After August 2021

Magnus Marsden

Professor of Social Anthropology, University of Sussex

By May 2021, it had become increasingly obvious that the government of Afghanistan and the political system it represented would not survive the year. Until then, the best-case scenario for government officials had been that the Afghan National Army was strong enough to control most if not all of the country’s urban centres. Yet the withdrawal by the US of the technical support it had offered to the army alongside the massive over-exaggeration by officials of the size of the Afghan army, meant there were few chances of Ashraf Ghani’s government retaining control of Afghanistan’s urban centres let alone its important rural hinterlands. Against this backdrop, the Taliban swept across the country in July and August and took control of Kabul on 15th August 2021.

There has been an improvement in the general level of security in Afghanistan since the departure of international forces and the return of the Taliban to power in Kabul. People now are able to travel across many more parts of the country than was possible during the years of the Taliban insurgency against NATO and the governments of Ashraf Ghani and Hamid Karzai. Simultaneously, however, the Taliban historically have viciously pursued their enemies. Since the Taliban takeover of 2021, former military and security officials and vocal opponents of their regime including former women MPs and journalists have been tortured and killed.

In terms of economy, it is widely reported that the Taliban have reduced the levels of corruption at Afghanistan’s major borders, making trade between the country and other parts of Asia easier. At the same time, however, international sanctions on the Taliban have decimated the baking sector and the economy more generally increasing unemployment rates massively and driving many families into extreme poverty. Restrictions on humanitarian aid as a result of sanctions has also led to a dramatic reduction in the scope of Afghanistan’s government and private hospitals, the staff of which often work for months without being paid.

There was some initial hope that the Taliban would seek to run the Afghan state and organise society in a different way than during their first period of government (1996-2001). Such hope – advocated by both international and Afghan actors who had supported talks mediated by US diplomat Zalmay Khalizad – has quickly receded. Once again, international actors peddle the simplistic idea that ‘Afghan culture’ (whatever that is) is fundamentally ‘tribal’ and conservative, and that such ‘culture’ explains the failure of the Western intervention in the country over the past twenty years.

As in the 1990s, women in Afghanistan today have endured the most of the Taliban’s policies. Having seized control of Kabul the Taliban immediately banned girls from accessing secondary school education, something they explained in terms of the security situation but have repeatedly failed to review. In the coming months, the Taliban also banned women from studying in the country’s universities as well as from working in the vast majority of types of employment. Women’s ability to move in public space has also contracted dramatically. In 2021, women living in Afghanistan’s cities not only worked but also increasingly enjoyed leisure activities in the many restaurants, cafes and parks. By 2023, women living in Afghanistan are only allowed to leave the home if accompanied by a close male relative – they are also banned from visiting parks, including even those designated specifically as being for women. There are divisions within the Taliban leadership on the movement’s social and moral policies. From time to time, key officials air in speeches differences with one another – especially on the thorny issue of girl’s education. To date, however, the movement’s hardline leadership maintains a tight grip on power and is unlikely to change its stance on key issues which have become a marker of their religious and political authority.

Is there an alternative to the Taliban?

Protests inside Afghanistan have largely been organised and led by women. Women activists have faced arrest and imprisonment having challenged restrictions introduced by the Taliban on women’s access to education and employment.

In the first months following the return to power of the Taliban, there was the expectation in some quarters that the country would see a major anti-Taliban resistance movement. Ahmad Massoud, the son of Afghanistan’s fiercely anti-Taliban former Minister of Defence (Ahmad Shah Massoud), initially sought to maintain a foothold in the country by launching the National Resistance Front (NRF) and seeking to defend the valley of Panjshir. Former government officials as well as section of the Afghan Army joined him. After failed negotiations between Massoud and the Taliban, Taliban forces entered Panjshir in August 2021. They brutally supressed the local population while Ahmad Massoud and his core supporters fled by helicopter to neighbouring Tajikistan. The NRF leadership remains in Tajikistan. They continue to issue statements challenging the legitimacy of the Taliban government and call for a moderate Islamic government in which women’s rights are protected. The NRF is also engaged in guerrilla fighting in the north of the country. To date, however, NRF fighters have not been able to make significant gains; indeed, key military commanders fighting for the NRF have been killed in recent months. The NRF is not the only organisation that has fought the Taliban on the ground; other movements have attacked Taliban fighters in Kandahar, Kabul and other cities. Overall, however, neither having international support nor controlling tracts of territory within Afghanistan, their impact on the Taliban’s grip on power remains minimal.

If movements that depict themselves as being in favour of democracy and human rights have thus far been at best a minor irritation for the Taliban government, then ISIS-Khorasan (the arm of ISIS active in Afghanistan) has launched a series of deadly attacks that have killed and wounded scores of ordinary Afghans. ISIS-Khorasan has targeted in particular the religious institutions of the country’s religious minorities, launching attacks against Shii and Hazara worshippers in mosques in Kabul, Kunduz, Herat, and Kandahar, and killing several members of the miniscule number of Sikhs and Hindus who continue to live in the country, most notably in an attack on a Sikh Gurdwara in June 2022. International actors tend to regard the threat posed by ISIS-Khorasan as a reason to support (if from afar) the Taliban government and its security apparatus.

The difficulties facing movements opposing the Taliban is not limited to those fighting on the ground. Afghanistan’s former political leadership is now scattered around the world. Key figures are based in the UAE and Turkey, as well as in various Western countries. Many Afghans living in the country and in the diaspora regard the governments led by Ashraf Ghani and Hamid Karzai as corrupt. Images of the palace-like homes they built in Afghanistan in videos captured by journalists and the Taliban have circulated widely on social media. It is not surprising then that many within and outside the country see the former leaders as the root cause of the collapse of the former government and the return to power of the Taliban. Afghanistan’s former leaders who fled Afghanistan in August 2021 lead comfortable lives in Istanbul, Ankara and Dubai while those who supported them must adapt to Taliban rule in Afghanistan, the increasingly hostile societies of Iran, Pakistan and Iran or life in exile in the West. As a result, Afghan political leaders who oppose the Taliban lack the degree of legitimacy they held in the early 2000s, including amongst those who were formerly their core supporters.

There is little in the way of unity between the multiple individuals and organisations opposing the Taliban. They are divided in terms of competing political and economic interests, as well as along the lines of ethnicity and religious sect. The division between leaders who depict themselves as representing Pashtuns and those whose core constituency are Tajiks is especially acute. Some leaders see Afghanistan’s problems as arising from its centralised system of governance; others accuse those making this argument as being closet secessionists. Opposition leaders abroad argue about the future political system of Afghanistan, a country to which they are unable to travel and in which they exert little influence on the ground. As a result, international actors have largely dismissed the possibility of these leaders ever being able to organise an effective opposition. Instead, international actors and many commentators from Afghanistan itself now hope that a new generation of politicians from Afghanistan will arise and be able to exert influence on the Taliban in the decades to come. While women from Afghanistan are playing a leading role in organising political activities outside of the country, the closure of universities and schools for women and girls in the country is likely to have serious implications for the gender profile of the next generation of Afghan politicians.

The outlook for the coming years is therefore bleak. A lack of international interest in Afghanistan in the context of the war in Ukraine, the dominance of the Taliban inside the country, and a divided, corrupt, dispersed and demoralised opposition that lacks legitimacy in the eyes of the country’s people all make a positive change in the country’s governance highly unlikely if not impossible. As on so many occasions in Afghanistan’s history, the absence of serious and continuous international engagement, diplomacy and justice, and of internal political dynamics driven by the pursuit of power and wealth means that the country’s future lies in the ability of its long-suffering people to endure difficult circumstances and build bridges with one another.